» Site Contents |

Manuscripts

Ferdowsi's Manuscript

We are told that Ferdowsi wrote two editions or redactions of his epic. The first was completed in 995 or 999 CE and the second in March 1010 CE. 2010 is the one-thousandth anniversary of the Shahnameh's final 1010 edition.

However, a manuscript of Ferdowsi’s epic, the Shahnameh, written in the poet’s own hand is not known to exist. The earliest surviving manuscripts known to us were written some two hundred years after the death of the poet around 1020 CE.

The various existing Shahnameh copies are all unique and no two copies have precisely the same textual content since scribes who wrote the manuscript copies were prone to error and editing.

Earliest Surviving Manuscript Copies Known

The earliest surviving Shahnameh manuscript copy that is known to us – and one which is incomplete – dates back to 1217 CE and resides today in Florence’s National Library (Biblioteca Nazionale). It was discovered as recently as 1977 by one Angelo Piemontese.

The next oldest known manuscript dates to c. 1276-1277 and is in the British Library or Museum (?). It is a single volume and contains no illustrations. About a hundred years ago, Britain and Russia effectively divided Iran as well as some of its treasures between themselves. Several Shahnameh manuscripts found their way into European hands as a consequence.

The earliest known illustrated Shahnameh codex dates from around 1300 CE. Many illustrated Shahnameh codices are no longer in bound form. Shamefully, several have had their pages taken apart by western ‘collectors’ (sic) seeking to maximize their resale profit. The dispersed pages now lie in private collections and museums.

Recent Manuscript Discovery in Beirut

|

| Mongol manuscript folio 1330s Tabriz Sindukht Becoming Aware of Rudaba's Actions Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. |

The most recent codex was discovered in 2005 – in battle scared Beirut. During a visit to the Bibliothèque Orientale (Oriental library) of Saint-Joseph University in Beirut, Lebanon, Prof. Moosavi of Tehran University had a Shahnameh manuscript copy handed to him on the very last day of his stay. Sadly, the manuscript’s colophon had been cut out – perhaps because the manuscript had at some point been stolen from its rightful owner. As a result, we can only make an educated guess about the date of its writing – which in the estimation of Iranian scholars was sometime between 1250 to 1350 CE. This dating, if correct, makes it one of the earliest Shahnameh manuscripts known to exist.

The text of the Beirut Shahnameh manuscript is written in four columns on both sides of 496 folios (sheets i.e. 992 pages) of thick yellowish (presumably handmade) paper (see figure 1). Generally, there are twenty-five lines of text on each page. The manuscript contains no illustrations.

While it is commonly believed that Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh consists of 60,000 couplets, authoritative manuscripts generally contain fewer than 50,000 couplets (100,000 lines). The higher number includes verses added by the scribes in later manuscripts. The number of the verses of the Beirut MS is estimated at between 48,023 and 48,101. Nevertheless, the Beirut Shahnameh is over three times the combined length of the Greek epics, the Iliad (15,693 lines) and the Odyssey (12,110 lines).

Illuminated Manuscripts

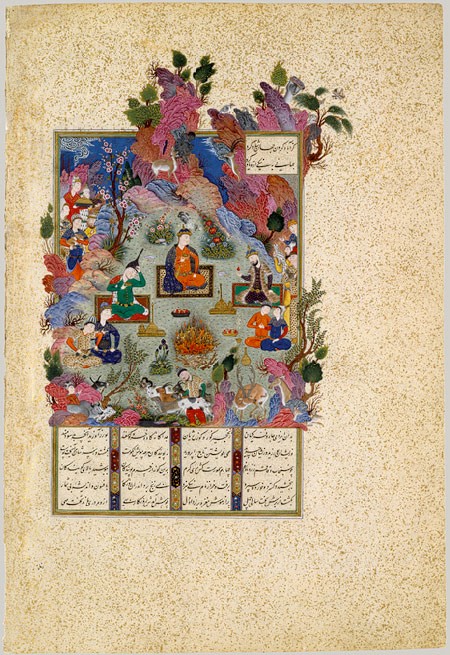

Generally speaking, the oldest manuscript copies discovered to date have no illustrations. At some point in their production, the Shahnameh manuscript copies began to include illustrations – commonly miniature watercolour paintings. While the earlier illustrated manuscripts have the artwork contained neatly within the borders of a container box itself within the written page (see figure 2), in later manuscripts, the illustrations effusively flow out their containers boxes (see figure 5). Trees begin to spread their branches into the margins and dragons seem poised – ready to consume heroes and text alike. At times the miniatures dominate the pages relegating the text to a second glance.

Western art collectors have raised the price of the manuscripts mainly because they fancy the illustrations. They have little interest in the text. To this end, some collectors have tragically resorted to cutting out the illustrations and discarding the text. As well, publishers have cropped the page images to show only illustrations and museums have matted pages so that the text is not visible. Even much of western scholarly interest in the Shahnameh focuses on the artwork. For a Zoroastrian, the medieval images and Arabic-Farsi naskh script, while elegant, hide the true treasure buried in the Parsi words.

The earliest known illustrated manuscript copies date back to the reign of the Mongol Ilkhan khans (1255 - 1335 CE) who occupied and established themselves in Iran for a century. The Ilkhanate was founded by Genghis' grandson Hulagu and was originally based on traditional Aryan lands occupied by Genghis Khan. Beginning with Mahmud Ghazan in 1295, the khans embraced Islam.

It became traditional for Mongol Ilkhan khans, and later the Timurid sultans (1363 - 1506 CE) and Safavid shahs (1502 - 1736 CE) to commission the production of a Shahnameh manuscript (and there was a school of art typical of each dynasty). These manuscripts are frequently known by their sponsors' names. The manuscripts are also known, sometimes infamously, by the names of their modern owners. During the times of the three dynasties noted above, there were two principle centres of art – Tabriz and Shiraz.

The following manuscripts have achieved some notoriety and are listed chronologically:

Great Mongol / Demotte Manuscript (Dispersed)

|

| Mongol manuscript folio 1330s Tabriz Sindukht Becoming Aware of Rudaba's Actions Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. |

Among the earliest illustrated manuscripts is the Great Mongol manuscript dating back to the 1330s Ilkhanid period (see above). It is a simple yet elaborate and luxurious manuscript. It is also known as the Demotte manuscript after Georges Demotte (1877-1923), the dealer and reseller responsible for its dismemberment and dispersal as individual pages.

When Demotte could not get an offer that met his profit objective, sometime between 1910 and 1915, he took the manuscript apart. He even resorted to splitting some folios (pages) with illustrations on both sides and selling the two resulting leaves individually.

|

| Mongol manuscript folio 1330s Tabriz Isfandiyar's funeral Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Joseph Pulitzer Bequest 1933 |

When Demotte pealed apart the pages – itself a feat – he mounted each illustration onto a new fabricated folio which he constructed by pasting an illustrated page segment to an unrelated text-only segment. Some pages were inevitably damaged and Demotte’s scheme resulted in irreparable mutilation, the joining of unrelated pages, and dispersal of pages with incomplete text.

The frontispiece and colophon that might have revealed information on the patron, the calligrapher, and the date and place of production are lost, and it is therefore not known with any certainty, where and when the manuscript was produced. By piecing together collateral evidence, researchers Oleg Grabar and Sheila Blair have surmised that the manuscript was possibly commissioned in Tabriz by the vizier Ghiyath al-Din ibn (son of) Rashid al-Din sometime between November 1335 (when he organized the appointment of Arpa r. 1335–36 as successor of Abu Sacid) and his death on May 3, 1336. (Reference: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

According to Grabar and Blair, the original manuscript probably consisted of two volumes of about 280 large (29 x 41 cm) handmade paper folios with 190 opaque watercolour illustrations.

Today, only 57 illustrations (A fifty-eighth illustration was destroyed in 1937 and is known only from a photograph) and several text pages are known to exist scattered among public and private collections including the Smithsonian, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harvard University's Fogg Museum, and Worchester Museum.

Bayasanghori (Baysonqori) Manuscript (Intact)

|

| Bayasanghori (Baysonqori) manuscript folio c 1430 CE Tabriz. Housed at Gelstan Palace, Tehran Faramarz son of Rostam mourns the death of his father and of his uncle Zavareh. |

The Bayasanghori (or Baysonqori) illuminated manuscript, resides at the Golestan Palace, Tehran, Iran, and is included in UNESCO's Memory of the World, register of cultural heritage items. The manuscript is dated c.1430 CE.

The patron of this manuscript was Prince Bayasanghor (Baysonqor) (1399-1433 CE), grandson of the founder of the Timurid dynasty, Timur (1336-1405 CE). The calligrapher of the manuscript was Maulana Jafar Tabrizi Bayasanghori (Baysonqori) and the artists were Mulla Ali and Amir Kalil. The binding was done by Maulana Qiam-al-Din.

The manuscript is in quarto format (38.26 cm), written in a minuscule Nasta'lip script on Chinese (Beijing) fawn-coloured hand-made paper from Khan Baligh. It consists of 700 pages with 31 lines of text per page and 21 illustrations. The covers are made from stamped leather, the outside being gold-plated with two lacquer-work borders. The preface contains an illustration of Ferdowsi in discussion with the poets of Ghazna.

According to page nine of the manuscript's introduction, the manuscript was copied from several prior manuscripts of the Shahnameh – copies that we now understand included legends penned by other poets who emulated Ferdowsi's style. As a result, the manuscript contains 58,000 verses making it one of the most voluminous. In the process, the scribes also edited the language, ostensibly to 'modernize' the language. The Bayasanghori (Baysonqori) manuscript has in turn served as the basis for subsequent manuscripts.

Tahmaspi / Houghton Manuscript (Dispersed)

Illuminated with 258 miniature paintings, the Tahmaspi (Tahmasbi) manuscript is one of the most lavish and well known of the Shahnameh manuscripts. Named after its patron Shah Tahmasp I (1524-1576 CE), the second monarch of the Safavid dynasty, the Tahmaspi manuscript was in 1576, given as a gift to either the Ottoman Sultan Selim or Sultan Murad III. Martin Dickenson and Stuart Welch, authors of The Houghton Shahnameh, and others, suggest that the manuscript may have been commissioned and started in 1522 or shortly thereafter. This would be during the reign of Tahmasp’s father, Shah Isma'il I.

Largely completed by 1540, the manuscript was produced at Tabriz in northern Iran over a thirty-year period by a variety of calligraphers and illustrators such as Mir Mosavar, Sultan Mohammad, Aqa Mirak, Dust Mohammad, Mirza Ali, Mir Seyed Ali, Mozafar Ali, Abdolsamad, and their assistants. Of the illustrators, Sultan Mohammad is most renowned. His miniatures display an evolution of style from one painting to the next.

The manuscript which had been housed in the Ottoman Royal Library and possibly the Qajar Royal Library, was at some point acquired by Edmond de Rothschild. In 1959, Rothschild sold the manuscript to Arthur Houghton, a member of a prominent New England and upstate New York business family, and president of Corning Glass Works.

|

| Tahmaspi or Houghton manuscript folio 308 v 1. Artist Dust Muhammad? Tabriz, c.1530. Auctioned Lot 43 10/15/1997 Sotheby's. Kay Khosrow fetes Rustam under the jewel-tree. |

To the horror of many, soon after Houghton acquired the book, he proceeded to take apart the 742 large (32 x 47 cm) folios with the intention of individually selling the illustrated pages containing the miniature paintings. Some of these he placed on display at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, and later donated 88 illustrated folios to the museum in order to reduce his tax liability (according to an article from Souren Melikian in Art and Auction magazine dated October 1994 quoted by Dr. Habibollah Ayatollahi).

|

| Tahmaspi or Houghton manuscript Artist Sultan Muhammad Tabriz, c.1530. Hushang, grandson of Gayumars. Feast of Sadeh |

In 1976, Houghton offered to sell the remaining pages to the Shah of Iran for US$20 million, an offer that the Shah refused. On November 16, 1976, Houghton had seven folios auctioned at Christie's in London. In a subsequent 1988 auction fourteen folios sold, with one selling for £253,000. In 2006, a folio was sold at Sotheby's auction house to the Aga Khan museum in Geneva for 904,000 Euros (US$1.7 million). The museum eventually acquired additional folios. [A folio from the Qavam al-Din manuscript produced in Shiraz by calligrapher Hassan b. Muhammad b. 'Ali Husaini al-Mausili in May 1341 CE; a colophon and five illustrated folios from a 1482 CE manuscript (ex Demotte) produced in Shiraz by calligrapher Murshid b. 'Izz al-Din; an illustrated folio from a manuscript sponsored by Sultan 'Ali Mirza Karkiya and produced by calligrapher Salik b. Sa'd in 1494 CE.]

The 118 folios that had not been sold by Houghton by the time of his death in 1990 were offered for sale by his foundation for Fr. 70 million. When the collection could not find a buyer at that price, Oliver Hoare, a British art dealer arranged an exchange of the folios with a painting, Lady No. 3 by Willem De Kooning (1952-53), owned by the Islamic Government of Iran – but one the Iranian government had removed from public display considering it lewd (in 1989, another one of De Kooning's paintings had sold for $18 million at an auction at Sotheby's).

Elation, Regret & Hope

A review of the literature on the various Shahnameh manuscript copies gives rise to a variety of emotions. On the one hand, elation that the manuscripts have survived and with them a heritage – a heritage that could very well have disappeared had it not been for Ferdowsi’s single-minded determination to fulfil his mission. On the other hand, regret that we do not know what happened to Ferdowsi’s own manuscript – if it has been destroyed or if it still exists, waiting to be discovered - and regret that the surviving manuscripts have been treated in such a cavalier manner by some of their owners. We must remain forever hopeful that there are more manuscripts waiting to be discovered, perhaps even Ferdowsi's own.

» Top