Contents

Zoroastrian

Cleansing & Purification

Ceremonies

Cleanliness & Purification

For a Zoroastrian, cleanliness is indeed close to godliness. Keeping clean with ritualized bathing and washing was part of not just a daily routine, but a routine for the different gahs / gehs, or divisions of the day as well. When a person was contaminated in some fashion - or as a preventative measure against any possible contamination - then a further process of purification was prescribed.

Cleanliness and purification involved not just people, but clothing and the physical space occupied or used by them.

|

| Cleanliness & purity in clothing and the covering of the mouth |

The cleansing prescriptions were especially pertinent in ancient times and in dry, dusty climes: daily bathing (nahn or nahan) were possible, the washing of hands and face before every meal and prayers for the five / four divisions of the day, the washing of hands, face and feet and the removal of shoes before entering a place of worship, the wearing of white undergarments and white ceremonial clothing, the covering of the face by priests (who were also physicians in ancient times), and the ritualized cleaning of a space or any implements (to prevent the spread of disease symbolized as the spread of evil), were all part of ritualized cleansing.

The purification prescriptions included the use of a disinfectant such as bull's urine (which though odd by today's standards, was one of the few readily accessible and effective disinfectants in ancient times), the smoke or aroma released during the burning of certain woods, and rituals to remove the evil eye.

The concepts behind cleanliness and purification involved the body, mind, spirit and soul - cleanliness and purity in both the physical and spiritual realms.

Cleansing & Purification Ceremonies

The cleansing and purification ceremonies prepare a person, space or article for a religious ceremony and include spiritual and physical cleaning.

Evil Eye & Protection Against Evil

A person who wishes another ill, is jealous, envious, or angry towards another person, is said to have the evil eye. The evil eye can have negative consequences for the target of the ill feelings and there are rituals to remove the ill effects of the evil eye. The rituals extend to generally removing all evil lurking around a person and protecting a person against evil.

The concept of the evil eye and removing the effect of the evil eye has no discernable foundation in Zoroastrianism other than the determination to combat evil in all its forms at all times. The rituals to ward off evil are nevertheless a pervasive part of various Zoroastrian ceremonies. Even though some may relegate the concept to superstition, the various rituals to remove the evil eye add interest and tradition to the ceremonies of which they are a part.

The methods used to remove and ward off evil are practiced differently by Zoroastrians with origins in Iran and India. Zoroastrians from Iran burn espand while Zoroastrians from India perform the achu michu ritual.

Burning Espand / Esfand

|

| Espand or Esfand Peganum Harmala Seed |

One method for removing the effects of the evil eye is the burning of espand/esfand seeds. This practice is popular among the Zoroastrians of Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan and indeed for the rest of the mainly Muslim population in these countries.

Espand commonly refers to the dried seed of Peganum harmala, a perennial herb shrub from the Zygophyllaceae or Caltrop family, sometimes mistakenly called wild or Syrian rue. Espand grows in the arid regions Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan and India (where it is called harmal or harmala) to a height of thirty to sixty centimetres (one to two feet).

The method of using espand is to sprinkle the seeds on a bed of hot charcoals (any source will do) in a handheld container or censer. As the esfand burns, it pops and crackles producing an aromatic smoke that adds to the mystique. The censer is circled seven times over the head of the person receiving the ritual.

|

| Espand over heat |

The name espand or esfand is the modern contracted form of the older Avestan name spenta armaiti meaning equanimity (see Amesha Spentas) and the name of an archangel. While the number seven corresponds to the divine heptads of God and the six archangels, the seven circles of the smoking censer around the recipient's head, also limits the amount of smoke inhaled by the recipient.

In Afghanistan and Tajikistan, the ritual is particularly popular for removing the evil eye from children, newborns and the mothers, as for people returning from funerals. The person performing the espand on someone is called the espandi and espandis can be found selling their services on the street to passers who feel the need to have the effects of the eye evil removed. One can perform the espand on oneself.

Often, the prayer is replaced by this short poem, considered by some to be a version of a Zoroastrian prayer with Shah Naqshband as a replacement for Spendarmand (a later form of Spenta Armaiti and an earlier form of Espand).

|

| Espand (Peganum Harmala) Sprig |

The Dari (Afghan) version is:

Espand balaa band

Barakati Shah Naqshband

Jashmi heach jashmi khaish

Jashmi dost wa dooshmani bad andish

Be sosa der hamin atashi taze.

The Farsi (Tajik) version is:

Espand balla band

Ba haq shah-e-naqshband

Chashm-e-aaish chashm-e-khaysh

Chashm-e-adam-e bad andaysh

Besuzad dar atash-e-taiz

... both of which roughly translate to:

Espand stop (band) evil (bla or balla)

With King Naqshband's blessings / command

Eyes of none, eyes of relatives

Eyes of friends, eyes of enemies

Burn in this glowing fire.

The mention of fire here brings up the various concepts and symbolisms behind fire in Zoroastrianism, one being its transformative nature and the second as a symbol of asha and wisdom's ability to overcome evil and ignorance represented by darkness.

Northwest of Iran in the country of Azerbaijan, the land of the eternal fires, espand is called uzarlik. According to Jean Patterson and Arzu Aghayeva, one vendor, Movsum Asgarov from Lankaran stated, "My uzarlik is gathered wild in the Khizi mountains. It must be taken from a very remote place, where a rooster's crow cannot be heard. Then its effect will be even stronger." The Khizi mountains are located a few hours' distance north of Baku on the road to Guba.

Asgarov added "You burn uzarlik and then inhale the scent. Also, when people around you smell this smoke, they are stripped of the ability to cause you harm. After that, spread the ash on your forehead and neck. That will banish black energy from your blood vessels."

While burning the uzarlik, he chants:

"Uzarliksan havasan, min bir darda davasan.

Na gadar ki, san varsan - dada, bala javansan"

Which translates as:

"Uzarlik, you are air, you are against a thousand and one grieves.

As long as you exist, fathers and sons will be young."

Another vendor told Jean and Arzu that he takes a small handful of uzarlik and salt which he circles around a person's head three times saying:

"Uzarliksan havasan, jami darda davasan.

Pis gozlari chikhardib ovujuna salasan."

This chant translates as:

"Uzarlik, you are air, you are against every grief.

Take out evil eyes and put them in the palm."

The uzarlik in the palm is then cast into a fire and burned. In Azerbaijan, black cumin (gara chorakotu) is also used in a manner similar to espand / uzarlik. When using black cumin, an odd number, say 7 or 13 seeds are burnt and the smoke is then spread around the home.

Those who partake of the espand ritual, attest to its efficacy especially during times of sorrow or depression, when it lightens the heart, raises the spirit and produces feelings of well-being, contentment and confidence.

The Espand plant was likely a member of the haoma family of 10,000 medicinal plants, the chief plant being ephedra.

|

| Espand (Peganum Harmala) Clump |

The espand plant is a rich natural source of five alkaloids, harmane, harmine, harmaline, harmalol and tetrahydroharmine (from the Indian name for the plant, harmal), the MAOI-A (monoamine oxidase inhibitor A), substances that have been used in modern medicine to treat clinical depression. The stems of the plant contain about 0.36% alkaloids, the leaves about 0.52%,the roots up to 2.5% and the seeds around 6%. The seeds have the highest concentration of alkaloids, but the rest of the plant could possibly have been used in conjunction with the other haoma / baresman medicinal and health promoting plants.

Extracts and smoke from the plant are known to have: analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties that also include being a central nervous system stimulant, antibacterial properties, effectiveness as a decoction for laryngitis, and the ability to reduce spermatogenesis and male fertility. Other properties include effectiveness against protozoans and malaria, and the ability to expel parasitic worms including tape worms. Anti-cancer and anti-tumour properties are reported including cytotoxicity to HL60 and K562 leukemia cell lines.

An extract produced by boiling espand in vinegar is used to alleviate toothache in central Iran.

A mixture of crushed espand seeds, honey, wine, chicken gall, saffron and fennel juice, is said to help strengthen weak vision.

In addition to relieving depression, the smoke from the seeds kills algae, bacteria, intestinal parasites, moulds, insects and inhibits the reproduction of the Tribolium castaneum beetle.

The root has be applied in some fashion to kill lice.

The seed produces a red dye that has also been used to alleviate the symptoms of certain skin diseases, skin cancer and subcutaneous cancers.

Individuals should never ingest the seed or extracts without expert guidance. Ingestion in excess can have harmful consequences, as can excessive inhalation of the smoke. The Zoroastrian guiding principle of moderation in lifestyle choices applies.

A comprehensive site on the web is: Erowid.

The Espand ritual of circling a censer over the head seven times, could that be the forerunner of the achu michu ritual described below.

Achu Michu

Purpose of the Ritual

|

| Achu Michu before a wedding ceremony performed at home in Mumbai The final step with a little water in the tray or sace / ses |

The achu michu is a ritual that performed by Indian Zoroastrians to remove the evil eye and any evil lurking around a person. It also cloaks a person with an aura of protection against the influences of the evil eye or lurking evil during a religious ceremony, thereby keeping the person spiritually pure.

With the addition of the tandorosti prayer, a prayer for a long, healthy and righteous life full of grace, the achu michu becomes a blessing ceremony that does not require the services of a priest. In Persian, tan means body and dorost means correct or healthy.

While the items used in the achu michu (coconuts, betel leaves and nuts) have been adapted from Hindu customs and have no explicit support or justification in Zoroastrianism, the ritual itself is likely a version of the espand ritual adapted after the Parsi migration to India. Regardless, it is an interesting tradition that adds to the various rituals of a ceremony. The symbolism, is that Zoroastrians are ever vigilant against evil and seek to walk the path of Asha or goodness.

With some families, the achu michu can be found being performed by the eldest woman of a family before a ceremony such as a navjote, wedding or jashan ceremony. Shirinmai Mistry informed this author that she believes the woman performing the ritual is one, "Closest to the child, i.e. the mother, at the time of the navjote/besna ceremony or the prospective mother/s-in-law at the time of the wedding" and further that the woman should be married and not a widow.

The ritual itself can be performed at the door before guests enter a home to celebrate or participate in an event that has religious significance or within the home in a designated spot cleaned and readied for the occasion. In the case of the navjote and wedding ceremonies it is performed after the nahan or ritual bath and immediately before a person enters the sacred space in which the ceremony is to be performed.

While the nahan or ritual bath, is a physical and spiritual cleansing ritual, the achu michu removes and protects the person against evil and the evil eye. The two ceremonies together cleanse and protect a person entering or participating in a religious ceremony or one that has religious significance.

The items used in the achu michu ritual are placed in a tray called the sace (also spelt 'ses'). For further information please see our page on the sace / ses.

The Achu Michu Ritual

The ritual starts with woman performing the achu michu and the recipient or recipients standing in front of one another either at the doorway or on a spot such a low stool called a patlo or yet an area decorated with chalk designs called rangoli. The officiating woman applies a tila mark (long for a man and round for a woman) of kunkun on the forehead of the recipient and presses rice in the palm of her hand on to the wet tila paste, to which the rice adheres.

|

| Achu Michu before a navjote or initiation ceremony The initiate's grandmother circles an egg around his head |

The officiating woman removes an egg from the sace, holds the egg in her right hand supported at the elbow with her left hand. She then circles her hand and egg around the heads of the receiver six times in a clockwise motion, and once in an anti-clockwise motion, for a total of seven circles after which she breaks the egg is then broken on the ground, or on a stone tile, symbolically destroying any collected evil, or as some believe - the evil eye. Shirinmai Mistry who we quoted earlier has a different opinion. She has never been made aware of the method we have just cited and feels the motion should not be anti-clockwise at any time.

The procedure is repeated with a coconut.

Next, the kutli (see above) or container of water is set aside and the tray containing the balance of the items is circled seven times and the contents cast aside. Finally, some water from the kutli is poured into the tray which is circled seven times as before, after which the water is sprinkled on both sides of the recipient or recipients. It is not uncommon for the officiating woman to crack her knuckles on the side of her head to mark the end of the process to extricate evil.

[Shirinmai Mistry adds a humorous note: "The last action is with water in the ses (sace) of course but there are rice grains in it too and that is the one which gets disposed off on both sides (left and right) of the feet of the person being welcomed. The egg of course breaks easy when hurled on the ground (unless of course it is a boiled one picked up by mistake from the fridge when an egg was forgotten to be loaded in the ses from the start! (Don't laugh - that has happened here and the ses I was holding up shook so much with laughter my golabus (gulabuz, rose-water container) went toppling off!) The coconut must be cracked open - and never used again - after all it is taking all the druj (evil, wickedness, deceit and lies) from the person over whose head it is waved around seven times."

And then a sombre note: "The cracking of knuckles (together with the motion of the hand of the

officiating woman) from the head of the recipient to the officiating woman's own temples, symbolizes the taking away of all ills from the recipient into the officiating woman's own self. It is a supreme gesture of sacrificing one's own health for the sake of someone beloved. Some people murmur a heartfelt "muru-ray!" meaning 'may I die over you!'"]

All the circling procedures above are design to absorb and destroy evil.

The closing of the ritual includes the woman performing the achu michu places a piece of rock crystal in the mouth of the recipient, in a sub-ritual called mithu-moonu or mouth sweetening to encourage sweet talk. Finally, she showers grains of rice over the heads of the recipient(s) as a blessing accompanied with wishes for health, happiness and contentment.

After the last achu michu action, the recipients may choose to touch the officiating woman's feet as a gesture of thanks, humility and respect. When the recipients start the motion of feet-touching, the woman performing the achu michu usually attempts to stop the feet-touching by gently pulling up on the upper arm of the recipient as a reciprocal gesture of humility - but the foot-touching usually proceeds. Alternatively, the two hug each other.

Nahan / Nahn Ceremony

|

| The start of the Nahan, the ritual cleansing bath |

The nahan (or nahn) is a ritual bath taken before a ceremony such as the Navjote or Sudreh-Pooshi initiation ceremony or a wedding ceremony. The mother also takes a nahan after childbrith.

In preparation for the bath, the person under the guidance of the officiating priest, recites a prayer (the baj) and then chews on a pomegranate leaf that the priest will have brought with him. After removing the chewed leaf, the person also either sips or places her or his lips to a small metal container containing nirang (consecrated white bull's urine called taro or gomez when not consecrated). The taro is ritually consecrated to nirang in advance and is believed to have cleansing properties (also see Darmesteter 5.5). The nirang (taro) ritual is part of an ancient practice when taro was used externally (for washing items and the body) and internally as a disinfectant before the advent of modern anti-bacterial agents. While strange today, thousands of years ago, the practice was an effective control against the spread of disease and saved lives. When nirang-taro is not available, pomegranate juice can be used as a substitute. The priest will have added to the nirang, a pinch of the bhasam or the consecrated ash from a fire at the fire-temple.

gomez or taro

Next, the priest and person undergoing the nahan together recite the prayers of repentance, the patet, at the conclusion of which the priest leaves the bathroom and stands outside the door while the person bathes (if possible with consecrated water from the well of a fire temple). For the orthodox, the bath is a shortened version of the bareshnum ceremony described below and involves a symbolic cleaning with taro, sand and consecrated water, followed by a regular bath of the whole body using water to which a few drops of consecrated water have been added. All these steps were of great importance in prior days. Today, the steps are of symbolic importance.

On concluding the bath, the person will say their kusti prayers (unless, the nahan is being performed before an initiation or navjote ceremony), clothe themselves and come out of the bath.

[A Zoroastrian bathes daily before reciting her or his prayers, and though this is not the ritual nahan described above, it is nevertheless seen by orthodox Zoroastrian as a part of their daily religious rituals.]

Bareshnum Ceremony

Prior to being invested with the articles of the first two levels priesthood, the Navar and Martab initiates undergo a ritual purification to cleanse body and soul, called the bareshnum. The Navar for instance, undergoes two nine-day-and-night bareshnum ceremonies. The first time the initiate undertakes the bareshnum, he does so to cleanse himself. The second cleansing is on behalf (niyat) of the person in whose memory he is becoming a priest.

During the nine days, the initiate sips nirang-taro (see above) (consecrated white bull urine) and body cleansing with bull urine that is not consecrated, a scrubbing with sand, and a thorough wash of the whole body using consecrated water (consecrated by adding drops of nirang and consecrated water) accompanied with ritual prayers.

The result of the bareshnum was a disinfecting, exfoliating and thorough cleansing.

Cleansing by Fire - Chahar-Shanbeh-Suri & the Seven Cleansing Fires

|

| Fire chalice |

Chahar-Shanbeh-Suri has become a popular rite observed by a large number of Iranians who may or may not be aware of its significance. Fire is viewed as transformative and cleansing in that it transforms all it consumes into a likeness of itself. Zoroastrians also see the temporal fire as a symbol of a spiritual flame - the source of the light of wisdom, vigour and goodness. The single fire used in the popular rite is representative of the seven cleansing and purifying fires described below. The following notes on The Rite of Fire or Chahar-Shanbeh-Suri are from our Nowruz page:

|

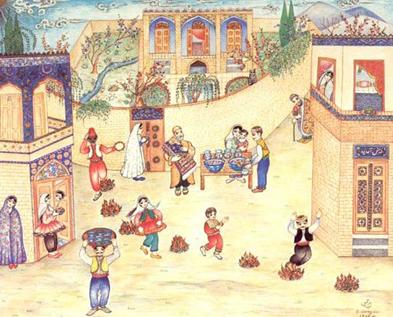

| Chahar Shanbeh Suri. Leaping over the fire |

Chahar Shanbeh Suri is the last Wednesday of the year before Nowruz. Chahar Shanbeh means Wednesday and suri means red, ruddy or glowing. On this day, the community gathers after sundown to light seven small bonfires which are kept burning through the night. Seven is an auspicious number in Zoroastrian tradition and several items of significance in Zoroastrianism are grouped in sevens. Above all, God and the six arch-angels number seven. After the seven bonfires are lit, people take turns to leap over the fires chanting "Sorkhie tu az man. Zardieh man az tu" loosely translated as "Give me your ruddy complexion. Take my sickly pallor." As a popular rite nowadays, often only one representative fire is lit with celebrants taking turns leaping over the fire.

Nowruz, New Year's Day, is celebrated on the Spring Equinox. Amongst the many symbolisms of fire, fire is representative of the Nowruz as well for reasons we outline below. The coming of spring brings hope for a future and enduring renovation of the world cleansed of all evil and one which will be accompanied by a resurrection of righteous souls. The cleansing of the souls will occur through a passage through molten metal in one tradition and fire in another. This future event is called Frasho-Kereti or Frashigird.

Seven Cleansing Fires

|

| Chahar Shanbeh Suri The seven cleansing fires and food sharing |

In the Frasho-Kereti tradition represented by Chahar Shanbeh Suri, all souls will pass through seven discerning fires that will allow the righteous to pass but which will consume the wicked. For the souls of the righteous, this passage will feel like wading through milk. The souls of the wicked will experience a final torment and cleansing of passing through molten metal. In one tradition, all souls either clean or cleansed will return to God. In another tradition, the souls of the righteous will be reunited with their bodies in a world that has achieved an enduring excellence through their prior efforts - through their good thoughts, good words, and above all, good deeds.

Perhaps the leaping over the fires at Chahar Shanbeh Suri is not just cleansing but an expression of the hope that the celebrant's soul will survive the ordeal of fire.

Sogdian Cleansing Custom

Sughdha (Sugd or Sogdiana) is the second nation listed the the Avesta's book of Vendidad - right after the Aryan homeland Airyana Vaeja. The region of Sugd today is divided between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan and lies directly north of the Pamirs. The people of ancient Sugd were Zoroastrians.

Sixth century CE (before the Islamic invasion) Byzantine historian Menander Protector informs us that that when a diplomatic mission of the Roman Byzantine Emperor Justin arrived at Sogdiana, the Turks (the Turks had begun their infiltration of Sogdiana by then and the poet Ferdowsi came to call the land Turan in the middle ages. However, many Turks adopted the area's Zoroastrian or Aryan customs and traditions) presented the delegation with iron (which we wonder had any significance with the tradition noted above of souls passing through molten metal) and then performed a cleansing ritual to ward off evil, the significance of which completely eludes Menander.

The welcoming Sogdians took the baggage of the diplomats at set them down in the middle of the gathered group. They then ran around the baggage beating a drum, ringing a bell carrying leaves (likely a descriptive error) of burning incense flaming and crackling (this sounds entirely like burning esfand - see above). The Sogdians also made the diplomats "pass through the fire" (we are unclear precisely what this means) "in the same manner they appeared to perform an act of purification upon themselves." Plano Carpini, a 13th century Italian traveller, and one of the first Europeans, who visited the Mongol court forty years before Marco Polo, wrote in his travelogue that "before we were taken to his court we were told we would have to pass between two fires, which we refused to do under any consideration. But they told us, 'Fear not, we only make you pass between these two fires lest perchance you think something injurious to our lord, or if you carry some poison, for the fire will remove all harm.' We answered them, 'Since it is thus we will pass through, so that we may not be suspected of such things.'" Elsewhere Carpini notes (as chronicled by Henry Yule who translated the travellogue of Marco Polo) "To be brief, they believe that by fire all things are purified. Hence, when envoys come to them, or chiefs, or any other persons whatever, they and the presents they bring must pass through two fires" to prevent the entry of any evil. If the ritual we have just described was a Mongol custom as well, then the congruence of the customs is quite remarkable. Buscarel, the French ambassador to Persia in 1289 so recounts having to pass through a purification fire.

» Go to Top